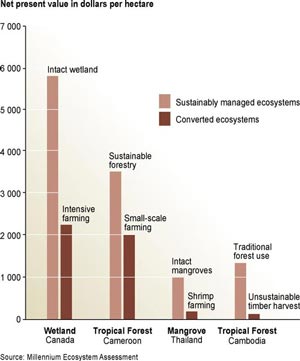

Box 2.2. Economic Costs and Benefits of Ecosystem Conversion

Relatively few studies have compared the total economic value of ecosystems under alternate management regimes. The results of several that attempted to do so are shown in the Figure. In each case where the total economic value of sustainable management practices was compared with management regimes involving conversion of the ecosystem or unsustainable practices, the benefit of managing the ecosystem more sustainably exceeded that of the converted ecosystem even though the private benefits—that is, the actual monetary benefits captured from the services entering the market—would favor conversion or unsustainable management. These studies are consistent with the understanding that market failures associated with ecosystem services lead to greater conversion of ecosystems than is economically justified. However, this finding would not hold at all locations. For example, the value of conversion of an ecosystem in areas of prime agricultural land or in urban regions often exceeds the total economic value of the intact ecosystem (although even in dense urban areas, the TEV of maintaining some “green space” can be greater than development of these sites) (C5).

- Conversion of tropical forest to small-scale agriculture or plantations (Mount Cameroon, Cameroon). Maintenance of the forest with low-impact logging provided social benefits (NWFPs, sedimentation control, and flood prevention) and global benefits (carbon storage plus option, bequest, and existence values) across the five study sites totaling some $3,400 per hectare. Conversion to small-scale agriculture yielded the greatest private benefits (food production), of about $2,000 per hectare. Across four of the sites, conversion to oil palm and rubber plantations resulted in average net costs (negative benefits) of $1,000 per hectare. Private benefits from cash crops were only realized in this case because of market distortions.

- Conversion of a mangrove system to aquaculture (Thailand). Although conversion for aquaculture made sense in terms of short-term private benefits, it did not once external costs were factored in. The global benefits of carbon sequestration were considered to be similar in intact and degraded systems. However, the substantial social benefits associated with the original mangrove cover—from timber, charcoal, NWFPs, offshore fisheries, and storm protection—fell to almost zero following conversion. Summing all measured goods and services, the TEV of intact mangroves was a minimum of $1,000 and possibly as high as $36,000 per hectare, compared with the TEV of shrimp farming, which was about $200 per hectare.

- Draining freshwater marshes for agriculture (Canada). Draining freshwater marshes in one of Canada’s most productive agricultural areas yielded net private benefits in large part because of substantial drainage subsidies. However, the social benefits of retaining wetlands arising from sustainable hunting, angling, and trapping greatly exceeded agricultural gains. Consequently, for all three marsh types considered, TEV was on average $5,800 per hectare, compared with $2,400 per hectare for converted wetlands.

- Use of forests for commercial timber extraction (Cambodia). Use of forest areas for swidden agriculture and extraction of non-wood forest products (including fuelwood, rattan and bamboo, wildlife, malva nuts, and medicine) as well as ecological and environmental functions such as watershed, biodiversity, and carbon storage provided a TEV ranging of $1,300–4,500 per hectare (environmental services accounted for $590 of that while NWFPs provided $700–3,900 per hectare). However, the private benefits associated with unsustainable timber harvest practices exceeded private benefits of NWFP collection. Private benefits for timber harvest ranged from $400 to $1,700 per hectare, but after accounting for lost services the total benefits were from $150 to $1,100 per hectare, significantly less than the TEV of more sustainable uses.

Source:

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment

Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Biodiversity Synthesis

(2005),

Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Biodiversity Synthesis

(2005),

Chapter 2, p.39

Related publication:

Other Figures & Tables on this publication:

Direct cross-links to the Global Assessment Reports of the Millennium Assessment

Box 1. Biodiversity and Its Loss— Avoiding Conceptual Pitfalls

Box 1.1. Linkages among Biodiversity, Ecosystem Services, and Human Well-being

Box 1.2. Measuring and Estimating Biodiversity: More than Species Richness

Box 1.3. Ecological Indicators and Biodiversity

Box 1.4. Criteria for Effective Ecological Indicators

Box 2. MA Scenarios

Box 2.1. Social Consequences of Biodiversity Degradation (SG-SAfMA)

Box 2.2. Economic Costs and Benefits of Ecosystem Conversion

Box 2.3. Concepts and Measures of Poverty

Box 2.4. Conflicts Between the Mining Sector and Local Communities in Chile

Box 3.1. Direct Drivers: Example from Southern African Sub-global Assessment

Box 4.1. An Outline of the Four MA Scenarios

Box 5.1. Key Factors of Successful Responses to Biodiversity Loss

Figure 3.3. Species Extinction Rates

Figure 1.1. Estimates of Proportions and Numbers of Named Species in Groups of Eukaryote Species and Estimates of Proportions of the Total Number of Species in Groups of Eukaryotes

Figure 1.2. Comparisons for the 14 Terrestrial Biomes of the World in Terms of Species Richness, Family Richness, and Endemic Species

Figure 1.3. The 8 Biogeographical Realms and 14 Biomes Used in the MA

Figure 1.4. Biodiversity, Ecosystem Functioning, and Ecosystem Services

Figure 2. How Much Biodiversity Will Remain a Century from Now under Different Value Frameworks?

Figure 2.1. Efficiency Frontier Analysis of Species Persistence and Economic Returns

Figure 3. Main Direct Drivers

Figure 3.1. Percentage Change 1950–90 in Land Area of Biogeographic Realms Remaining in Natural Condition or under Cultivation and Pasture

Figure 3.2. Relationship between Native Habitat Loss by 1950 and Additional Losses between 1950 and 1990

Figure 3.3. Species Extinction Rates

Figure 3.4. Red List Indices for Birds, 1988–2004, in Different Biogeographic Realms

Figure 3.5. Density Distribution Map of Globally Threatened Bird Species Mapped at a Resolution of Quarter-degree Grid Cell

Figure 3.6. Threatened Vertebrates in the 14 Biomes, Ranked by the Amount of Their Habitat Converted by 1950

Figure 3.7. The Living Planet Index, 1970–2000

Figure 3.8. Illustration of Feedbacks and Interaction between Drivers in Portugal Sub-global Assessment

Figure 3.9. Summary of Interactions among Drivers Associated with the Overexploitation of Natural Resources

Figure 3.10. Main Direct Drivers

Figure 3.11. Effect of Increasing Land Use Intensity on the Fraction of Inferred Population 300 Years Ago of Different Taxa that Remain

Figure 3.12. Extent of Cultivated Systems, 2000

Figure 3.13. Decline in Trophic Level of Fisheries Catch since 1950

Figure 3.14. Estimated Global Marine Fish Catch, 1950–2001

Figure 3.15. Estimates of Forest Fragmentation due to Anthropogenic Causes

Figure 3.15. Estimates of Forest Fragmentation due to Anthropogenic Causes

Figure 3.15. Estimates of Forest Fragmentation due to Anthropogenic Causes

Figure 3.15. Estimates of Forest Fragmentation due to Anthropogenic Causes

Figure 3.15. Estimates of Forest Fragmentation due to Anthropogenic Causes

Figure 3.15. Estimates of Forest Fragmentation due to Anthropogenic Causes

Figure 3.16. Fragmentation and Flow in Major Rivers

Figure 3.17 Trends in Global Use of Nitrogen Fertilizer, 1961–2001 (million tons)

Figure 3.18 Trends in Global Use of Phosphate Fertilizer, 1961–2001 (million tons)

Figure 3.19. Estimated Total Reactive Nitrogen Deposition from the Atmosphere (Wet and Dry)

in 1860, Early 1990s, and Projected for 2050

Figure 3.20. Historical and Projected Variations in Earth’s Surface Temperature

Figure 4. Trade-offs between Biodiversity and Human Well-being under the Four MA Scenarios

Figure 4.1. Losses of Habitat as a Result of Land Use Change between 1970 and 2050 and Reduction in the Equilibrium Number of Vascular Plant Species under the MA Scenarios

Figure 4.2. Relative Loss of Biodiversity of Vascular Plants between 1970 and 2050 as a Result of Land Use Change for Different Biomes and Realms in the Order from Strength Scenario

Figure 4.3. Land-cover Map for the Year 2000

Figure 4.4. Conversion of Terrestrial Biomes

Figure 4.5. Forest and Cropland/Pasture in Industrial and Developing Regions under the MA Scenarios

Figure 4.6. Changes in Annual Water Availability in Global Orchestration Scenario by 2100

Figure 4.7. Changes in Human Well-being and Socioecological Indicators by 2050 under the MA Scenarios

Figure 6.1. How Much Biodiversity Will Remain a Century from Now under Different Value Frameworks?

Figure 6.2. Trade-offs between Biodiversity and Human Well-being under the Four MA Scenarios

Table 1.1. Ecological Surprises Caused by Complex Interactions

Table 2.1. Percentage of Households Dependent on Indigenous Plant-based Coping Mechanisms at Kenyan and Tanzanian Site

Table 2.2. Trends in the Human Use of Ecosystem Services and Enhancement or Degradation of the Service Around the Year 2000 - Provisioning services

Table 2.2. Trends in the Human Use of Ecosystem Services and Enhancement or Degradation of the Service Around the Year 2000 - Regulating services

Table 2.2. Trends in the Human Use of Ecosystem Services and Enhancement or Degradation of the Service Around the Year 2000 - Cultural services

Table 2.2. Trends in the Human Use of Ecosystem Services and Enhancement or Degradation of the Service Around the Year 2000 - Supporting services

Table 6.1. Prospects for Attaining the 2010 Sub-targets Agreed to under the Convention on Biological Diversity