Langues:

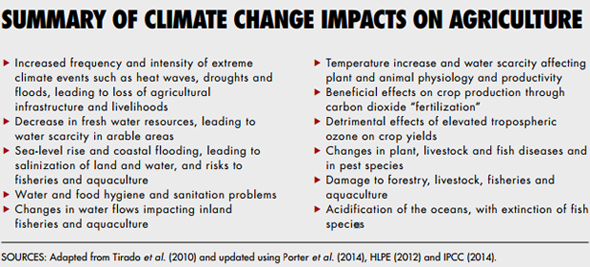

Global food demand in 2050 is projected to increase by at least 60 % above 2006 levels, driven by population and income growth, as well as rapid urbanization. In the coming decades, population increases will be concentrated in regions with the highest prevalence of undernourishment and high vulnerability to the impacts of climate change.

Therefore, a broad-based transformation of food and agriculture systems is needed and without adaptation to climate change, it will not be possible to achieve food security for all, and to eradicate hunger, malnutrition and poverty.

The time to invest in agriculture and rural development is now. The challenge is garnering diverse financing sources, aligning their objectives to the extent possible, and creating the right policy and institutional environments to bring about the transformational change needed to adapt to climate change, and contribute to limiting greenhouse gas emissions.

This report identifies the strategies, financing opportunities, and data and information needs. It also describes transformative policies and institutions that can overcome barriers to implementation.

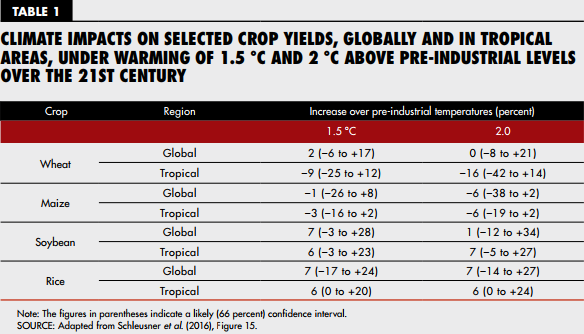

Farmers, pastoralists, fisher folk, and community foresters depend on activities that are closely linked to climate, and these groups are the most vulnerable to impacts if climate change. These impacts translate into more extreme and frequent weather events, heat waves, droughts and sea-level rise, and are alarming on agriculture and implications for food security. A plausible scenario would see – even in the medium term – widespread instances of abrupt non-linear changes, making adequate adaptation by the agriculture sectors almost impossible in many locations and causing drastic declines in productivity.

Climate change will also exacerbate stresses (overfishing, habitat loss and water pollution, …) on fisheries and aquaculture - which provide at least 50 % of animal protein to millions of people in low-income countries. Warmer water temperatures are likely to cause the extinction of some fish species, a shift in the habitat ranges of others, and increased risks of disease throughout the production chain.

More acidic world’s oceans owing to increases in levels of atmospheric CO2 will have severe consequences on fisheries depending on shellfish and squid, mangroves and coral reef systems, as well as on the frequency and intensity of storms, hurricanes and cyclones that harm aquaculture, mangroves and coastal fisheries.

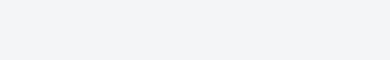

While impacts will vary across countries and regions, they will become increasingly adverse over time and potentially catastrophic in some areas. In tropical developing regions, adverse impacts are already affecting the livelihoods and food security of vulnerable households and communities. Until about 2030, global warming is expected to lead to both gains and losses in the productivity of crops, livestock, fisheries and forestry, depending on places and conditions.

But beyond 2030 the negative impact of climate change on agricultural yields will become increasingly severe in all regions. The most important impacts will be on animal productivity, animal health and biodiversity, the quality and amount of feed supply, and the carrying capacity of pastures.

Unless action is taken now to make agriculture more sustainable, productive and resilient, climate change impacts on agriculture will seriously compromise food production, and affect food availability by reducing the productivity of crops, livestock and fisheries. It will also hinder access to food by disrupting the livelihoods of millions of rural people who depend on agriculture for their incomes.

Among the most vulnerable will be those who depend on agriculture for their livelihood and income, particularly smallholder producers in developing countries and would be biggest in sub-Saharan Africa, partly because its population is more reliant on agriculture.

With climate change, the population living in poverty could increase by between 35 and 122 million by 2030 relative to a future without climate change. In the livestock sector, the general adoption of sustainable practices could cut livestock methane emissions by up to 41 % and could also increase productivity through better animal feeding, animal health and herd structure management.

Carbon dioxide emissions from agriculture are mainly attributable to losses of above and below ground organic matter through changes in land use (e.g. conversion of forests to pasture or cropland), and land degradation (e.g. caused by over-grazing). Soils are pivotal in regulating emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases. Increasing stocks of soil organic carbon improves crop yields and builds resilience to drought and flooding.

The bulk of direct emissions of methane and nitrous oxide are the result of enteric fermentation in livestock, rice production in flooded fields, and application of nitrogen fertilizer and manure.

The greatest potential for reducing nitrous oxide emissions is to improve crop production and fertilizer management, while these also reduce input costs by achieving a reduction in emission intensities. For example, alternate wetting and drying of rice fields reduces methane emissions from paddies by 45 %, while saving water and producing yields similar to those of fully flooded rice.

Meanwhile, although improvements in carbon and nitrogen management reduce emissions, they are likely to be driven by adaptation and food security objectives, rather than by climate impact mitigation goals.

Further CO2 emissions from the food system as a whole, are generated by the manufacture of agrochemicals, fossil energy use in farm operations, and by post-production transportation, processing and retailing.

Meanwhile, efforts by the agriculture sectors to contribute to a carbon-neutral world are leading to competing demands on water and land used to produce food and energy, and to forest conservation initiatives that also reduce greenhouse gas emissions. These efforts will also limit land available for crop and livestock production.

In order to manage agriculture for food security under the changing of global warming, FAO has developed the “Climate-Smart Agriculture” (CSA) approach with three objectives: sustainably increasing agricultural productivity to support equitable increases in incomes, food security and development; increasing adaptive capacity and resilience to shocks from farm to national level; and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Accordingly, the FAO identified four main challenges:

In this context, five key principles were identified that should guide the global transition to sustainability:

Changes will need to be made in a way that does not jeopardize the capacity of the agriculture sectors – crops, livestock, fisheries and forestry – to meet the world’s food needs. Hunger, poverty and climate change must be tackled together. What is needed is a reorientation of agricultural and rural development policies that resets incentives and lowers the barriers to the transformation of food and agricultural systems. Adaptation through sustainable intensification and agricultural diversification may have to be combined, therefore, with the creation of off-farm opportunities, both locally and through strengthened rural-urban linkages.

Smallholder farm families in developing countries – some 475 million –require greater access to technologies and information to adjust their production systems and practices to climate change making the livelihoods of rural populations more resilient. Intelligent investments can deliver transformative change and enhance the prospects and incomes of the world’s poorest while buffering them against the impacts of climate change.

Adequate access to credit for investment and markets, but also action to eliminate legal, socio-cultural and mobility constraints on rural women are also actions to be performed.

Increasing resource-use efficiency, cutting the use of fossil fuels and avoiding direct environmental degradation will also save farmers money, enhance productivity sustainably, and reduce dependence on external inputs. Rebalancing diets towards less animal-sourced foods would make an important contribution in this direction, with probable co-benefits for human health.

Equally important, about one-third of all food produced in the world is lost or wasted post-harvest. Reducing food losses and waste would improve the efficiency of the food system and reduce both pressure on natural resources and emissions of greenhouse gases.

Farmers can further enhance their resilience through diversification, which can reduce the impact of climate shocks on income and provide households with a broader range of options when managing future risks.

One form of diversification is to integrate production of crops, livestock and trees – for example, some agroforestry systems use the leaves of nitrogen fixing leguminous trees to feed cattle, use manure to fertilize the soil, and grow pulses to provide extra protein during periods of seasonal food insecurity.

By ensuring predictability and regularity, social protection instruments enable households to better manage risks and engage in more profitable livelihood and agricultural activities. Such programmes, which guarantee minimum incomes or access to food, should be aligned with other forms of climate risk management.

Comprehensive risk management strategies require understanding of the robustness of different risk management instruments under climate uncertainty. They also require coordination of actions by public, private and civil society sectors, from global to local levels.

In responding to climate change, international cooperation and multi-stakeholder partnerships are essential. For example, climate change will lead to new pests and disease problems and increase the risks of their transboundary movement. Strengthened regional and international cooperation will facilitate information and knowledge sharing to manage common resources such as fish stocks, and to conserve and utilize agro-biodiversity. Particular attention needs to be paid to developing heat- and drought-tolerant varieties for tropical countries, but also for temperate countries with already high temperatures during their growing seasons.

Cooperation is also needed to close gaps in our knowledge of climate change impacts on agriculture, food security and nutrition, to evaluate the scalability and economic viability of sustainable farming practices and to assess the ecological footprint of food systems at large.

In order to allow food producers to access the inputs and know-how needed for climate change adaptation and to be able to sell the products of their activities, it will be important to create firm links between smallholders and local, national and regional markets.

To assist its members, FAO is helping to reorient food and agricultural systems in countries most exposed to climate risks, with a clear focus on supporting smallholder farmers. It works in all its areas of expertise, pursuing new models of sustainable, inclusive agriculture:

FAO also provides guidance on including genetic diversity in national climate change adaptation planning, and has joined forces with the United Nations Development Programme to support countries as they integrate agriculture in adaptation plans and budgeting processes. FAO also helps link developing countries to sources of climate financing.

There is a general lack of coordination and alignment of agricultural development plans and actions that address climate change and other environmental problems. This leads to an inefficient use of resources and prevents the integrated management required to address climate change threats.

Smallholders, on the path to sustainable agriculture, face a broad range of barriers such as limited access to markets, credit, extension advice, weather information, risk management tools and social protection.

The adoption by farmers of improved practices is indeed often hampered by policies that perpetuate unsustainable production practices rather than those that promote resource-use efficiency, soil conservation and reduction in intensity of agriculture’s own greenhouse gas emissions.

In 2015, developed and major developing countries spent more than US$ 560 billion on agricultural production support, including subsidies on inputs and direct payments to farmers. Such measures may induce inefficient use of agrochemicals and increase the emissions intensity of production. More climate finance needs to flow to agriculture to fund the investment cost associated with the necessary large-scale transformation of this sectors and the development of climate-smart food production systems.

Gender issues need also to be addressed – social norms often prevent women from pursuing off-farm activities. Women, who make up around 43 % of the agricultural labour force in developing countries, are especially disadvantaged, with fewer endowments and entitlements than men. They also have more limited access to information and services, gender-determined household responsibilities, and increasingly heavy agricultural workloads owing to male out-migration. For example, a shift to more resilient intercropping systems has sometimes cost women their control over specific crops. They need to be better informed of the existing financial, institutional and policy barriers.

The adoption of improved management practices will help to achieve a significant reduction in the number of food insecure. However, improvements in infrastructure, extension, climate access to credit and social insurance, which are at the heart of rural development, are all needed in order to foster the adoption of improved practices and the diversification of rural livelihoods.

Policy frameworks need to be drastically modified to align agricultural development, food security and nutrition, and climate stability objectives. Policy-making for agriculture under climate change should start from an understanding of those drivers influencing productivity, of the degree of conservation, or depletion, of natural resources, and their impacts on farmers’ livelihoods and the environment. The Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs), which formed the basis of the 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change, are to become Nationally Determined Contributions. An area with potential for policy realignment is the redesign of agricultural support measures in a way that facilitates, rather than impedes, the transition to sustainable agriculture.

Increasing water use efficiency in agricultural systems under climate change may also require action in the fields of policy, investment and water management, and institutional and technical changes applied at different scales: on fields and farms, in irrigation schemes, in watersheds or aquifers, in river basins, and at the national level.

Private investment is the most important source of agricultural investment. Although more climate finance is needed for the transformation envisioned by this report, additional funding will also require improving countries’ capacity to make things happen on the ground. Systemic capacity constraints currently hamper developing country access to and effective use of climate finance for agriculture.

This “capacity gap” in policy-making and institutional development, which can manifest itself at both funding and receiving ends, hinders support for the transition to sustainable agriculture. Closing these capacity gaps should be made a priority by funders and countries alike, so that climate finance can serve its transformative role for food and agriculture.

Additional finance from public sources, as well as customized financial products, will require a significant increase in the amount of finance available, and more flexible conditions, such as repayment schedules adjusted to cash flows. This approach would allow farmers to make the investments that maintain current yields using fewer resources, and apply climate-smart practices and technologies that increase resilience while reducing emissions. Improving the enabling environment is needed for the vast majority of smallholder farmers, who are effectively disenfranchised from climate financing and denied opportunities for investing in productive activities that would improve their livelihoods.

Internased strategically to build the enabling environment essential for climate-smart agricultural development, to ensure that public agricultural investment is climate-smart, and to leverage private finance – could become an important catalyst for climate change adaptation and mitigation.

By filling the financing gap and catalysing investment, climate finance can strengthen risk management mechanisms, foster development of appropriate financial products, and address the capacity constraints of lenders and borrowers. Therefore, it is crucial to strengthen the enabling environment for climate-smart agricultural investments, mainstream climate change considerations in domestic budget allocations and implementation, and to unlock private capital for climate-smart agricultural development.

Climate finance could help address the funding gap by demonstrating the viability of climate smart agricultural investments, and designing and piloting innovative mechanisms to leverage additional sources of investment.

Until that happens, the climate financing needed for investment in smallholder agriculture will continue to be inadequate, with serious consequences in terms of loss of livelihoods and increased food insecurity.

This summary is free and ad-free, as is all of our content. You can help us remain free and independant as well as to develop new ways to communicate science by becoming a Patron!